The Australian Paradox

Professor Jennie Brand-Miller and Dr Alan Barclay

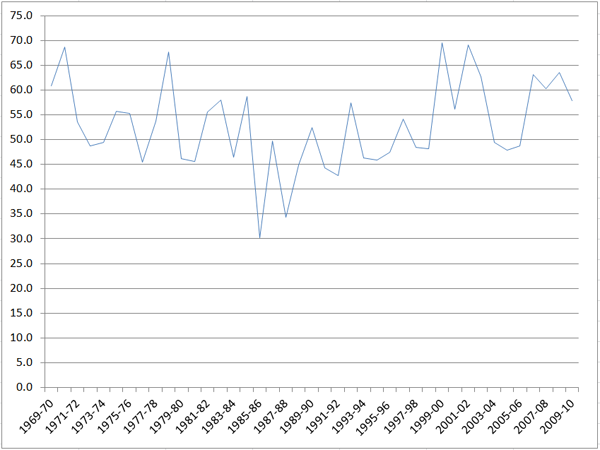

Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences

A crude analysis of Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARE) ‘sugar availability’ data has led some to believe that Australians have been consuming more sugar since the early 1980’s and that this is the main reason behind the current overweight and obesity epidemic in this Australia.

There are many flaws with this argument:

1) It is inappropriate to use ABARE derived ‘sugar availability’ data as an estimate of human sugar consumption. ABARE data have been used by an Australian economist to produce a simple estimate of total ‘sugar availability’, which is not equivalent to the apparent consumption of sugar by humans. To our knowledge, ABARE ‘sugar availability’ data have never been utilised in any official Australian Government Department of Health documents, or any other peer-reviewed health-related document, in the form presented by the economist, as it is not considered a valid estimate of human consumption. Perhaps coincidentally, the only place that we are aware that these 'sugar availability' data are used is in the books of lawyer David Gillespie that perhaps unsurprisingly vilify sugar.

2) ‘Sugar availability’ data suggests that Australians were consuming approximately the same amount in the early-to-mid 1970’s as they are now. If the economists hypothesis about sugars and overweight/obesity was true, then based on his ‘sugar availability’ analysis, there would have been an approximately equal number of overweight/obese people living in this nation in the early-to-mid 1970’s as there is now. However, rates of overweight and obesity more than doubled over the same period.

3) ‘Sugar availability’ is a crude measure and does not take into account changes in Australia’s population structure over the past few decades. The proportion of adults living in Australia has increased from 2/3 to 3/4 of the total population from the early 1970's until now, and as a population we are significantly taller (and heavier). Therefore sugar availability per kg body weight is even less than the crude analysis suggests.

4) ‘Sugar availability’ data are at odds with a large body of published scientific evidence. For example, the current Dietary Guidelines for Australians quote the Australian Bureau of Statistics apparent consumption data and notes the declining per capita consumption since World War 2 (page 175):

"Apparent consumption has fallen by about 15 per cent from prewar levels, or by 23 per cent from the post–World War 2 peak reached in 1948"

Furthermore, Table 1.9.6 (page 180) clearly shows that the percentage of total energy from sugar decreased or remained constant between 1983 and 1995 in Australian adults.

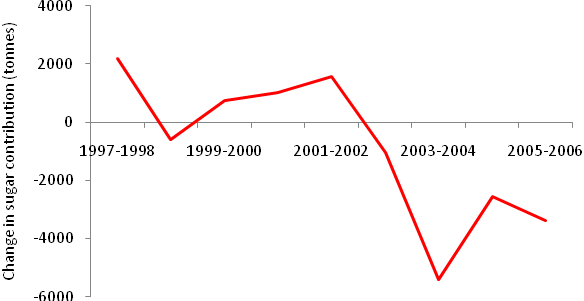

5) Australians are drinking more water and diet drinks and less sugar sweetened beverages, and many companies have reduced the sugar content of those beverages. The total amount of sugars from Sugar Sweetened Beverages (SSBs) has decreased since the mid 1990’s in Australia and Australians are replacing SSBs with bottled waters, non-nutritively sweetened (diet) beverages and reduced sugar alternatives.

Annual change in contribution of nutritively-sweetened carbonated soft drinks to total added sugar in the Australian food supply*

6) A newly published analysis by Green Pool Commodity Specialists lists the following additional issues with ABARE data.

1. The data are driven by Australian raw sugar production and exports, and therefore overstate refined sugar usage by 8.7 %. Why? Because in the refining process, raw sugar loses around 8.7% of its weight, as water and various impurities are discarded as steam and molasses. By comparison, sugar in ABS’ series is based on refined sugar total usage.

2. ABARE data are exceptionally volatile, a factor driven by production, stocks and export quantity variability. The measure takes no account of Australia’s raw sugar stock variation year-on-year let alone variation in refined sugar stocks.

3. It understates consumption by disregarding imports of refined sugar into Australia.

4. It disregards imports and exports of sugar-containing products for Australia.